Why Data Centers Are Switching to High-Voltage DC Power

The 19th-century Current Wars are getting a 21st-century sequel.

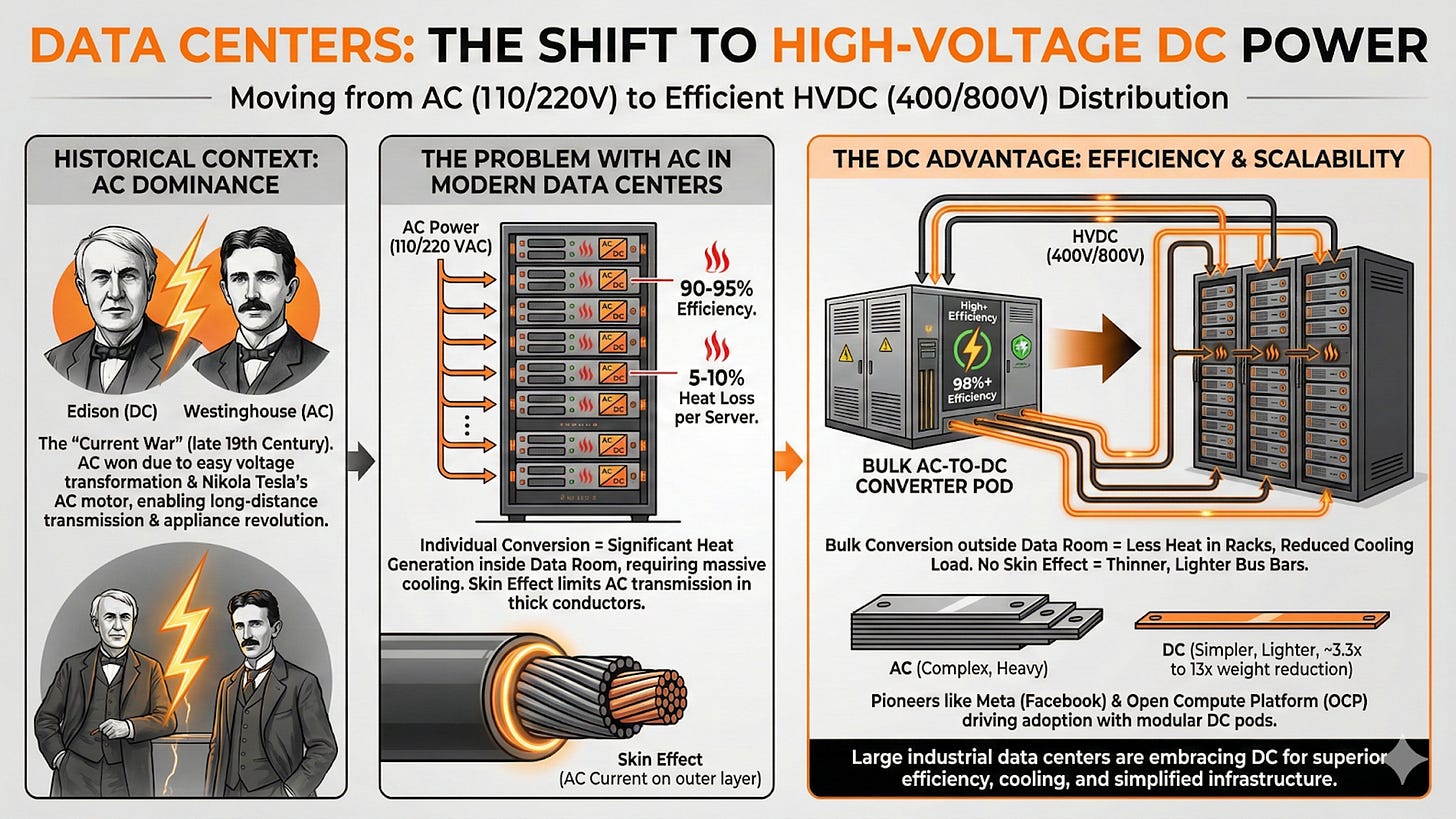

One of the areas that The Fusion Report has focused on over time is data centers and their role in the evolution of the utility grid (both positive and negative) in the developed world, particularly in the United States. One of the more interesting aspects of this is the shift in the power distribution of data centers from AC power (usually 110 VAC or 220 VAC at the server) to high-voltage DC power (typically 400 VDC or 800 VDC at the server). In this article, we will explore the reasons why this shift is being made, who is pioneering it, and the benefits.

DC vs AC – The Current Wars Are Still Alive In The 21st Century

In the late 19th century (at least in the US), there was an event known as “The Current War” (which was made into a pretty good movie in 2017). The “Current War” was about the rivalry between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse over how best to supply electricity to homes in the US, with Westinghouse advocating for alternating current (AC) and Edison pushing direct current (DC). The primary weakness of DC for electrical distribution was the difficulty of converting it between high and low voltages, an issue that was easily addressed in the late 1880s with transformers. The result was that DC power distribution systems of the 1880s lost significant amounts of energy to resistive heating, limiting the distances at which DC electricity could be transmitted.

However, the nail in the coffin for DC power distribution was Nikola Tesla’s invention of the AC motor in 1888. This motor, purchased along with Tesla’s AC patent portfolio by Westinghouse, was then used by Tesla. These technologies enabled the creation of hundreds of machines, appliances, and other labor-saving devices, thereby starting the electrical revolution we live in now.

The Evolution of the Data Center and How It Is Powered

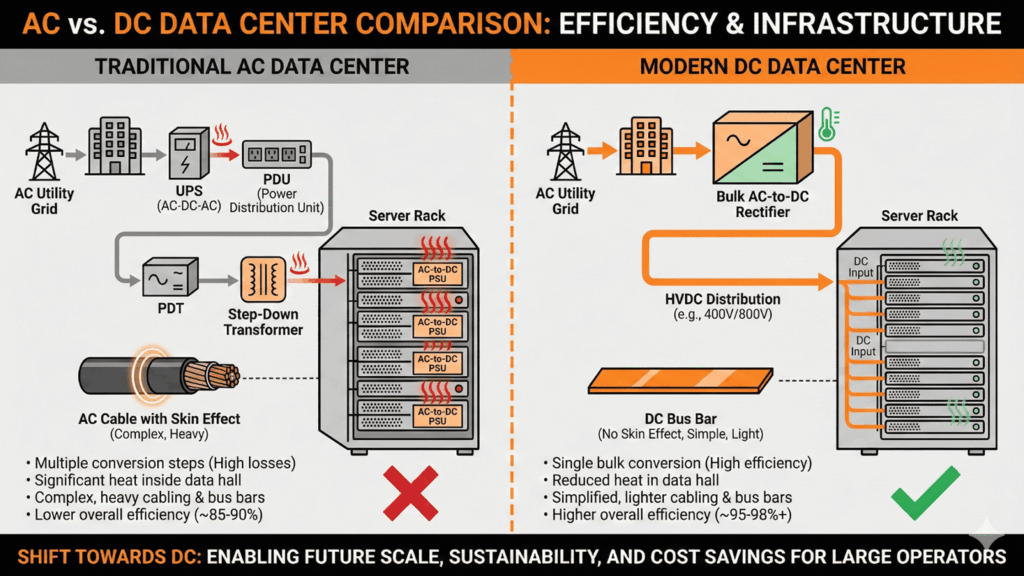

Like most electrical devices since the 1880s, data center devices such as servers, networking switches, and other data center equipment are powered by AC electricity (in the US, this is typically 110 VAC or 220 VAC, with 220 VAC used in both single-phase and three-phase). However, like many things since the 1880s, DC power has evolved considerably since the 1880s. Today, the advent of solid-state electronics has significantly simplified the conversion of DC electricity across multiple voltage ranges, with voltages easily into the hundreds of kilovolts (kV) and even past 1 megavolt (1 MV). The graphic above from 2022 illustrates this trend, but understates the trend in 2025.

More importantly, DC electricity has always avoided the “skin effect” that impacts the transmission of AC electricity, which limits how much power you can put into an AC transmission line. For instance, 60 Hz AC voltage is only carried on the outer 8.5mm of a wire; not an issue for a typical household wiring (which has a diameter of roughly 2.05mm), but has a significant impact on thicker conductors such as high-voltage long-distance transmission lines with typical diameters of 100mm, or bus bars in server racks. The usual approach for transmission lines is to use multi-strand cables; for bus bars, it typically involves more complex bus bar geometries, such as laminated and/or hollow bus bars. However, even with these technologies, distributing 110 VAC or 220 VAC power in server racks at power ratings approaching 100 kV is problematic, requiring hundreds of pounds of copper per rack. For 400 VDC or 800 VDC, the weight of the bus bars (which is proportional to the square of the current going through them) drops by a factor of roughly 3.3X for 400 VAC, and by over 13X for 800 VDC.

Top Ten Reasons to Move to DC Data Centers

The other primary drivers towards DC power distribution in data centers are cooling and efficiency. Like most things in technology, bigger is usually more efficient, which is absolutely true for AC-DC power conversion. Today, AC-powered servers individually convert their incoming AC power into DC, with a typical efficiency of 90%-95%. The remaining 5%-10% is converted into heat by the power supply. For a 1,000-watt server, the remaining 5%-10% equates to 50-100 watts, roughly the same as a home curling iron. However, when you put 20 servers into a rack, this produces 1,000-2,000 watts of heat from power conversion alone, which must be removed from the rack.

One of the most significant advantages of DC data centers is that it allows the data center architects to consolidate the AC-to-DC conversion process outside the data rooms (where the servers are located). This both removes the AC-to-DC heat generated from the data room, reducing the cooling required there. Moreover, it allows the AC-to-DC power conversion to happen “in bulk”, where it is more efficient (and remember, even a 1% efficiency gain in a 100 megawatt (MW) data center equals 1MW, enough to power several server racks.

Data centers are moving toward DC power mainly to cut conversion losses, reduce space and cooling needs, and better support high‑density AI and renewable integration. The shift is evolutionary, often starting with rack‑level or HVDC distribution rather than full end‑to‑end DC.

Higher end‑to‑end efficiency – DC architectures remove several AC–DC and DC–AC conversion stages (UPS, PDU transformers, server PSUs), eliminating 7–20% of energy loss in typical AC chains. Lab and field demos show 10–20% total facility energy savings when DC is adopted broadly in distribution.

Lower cooling load – Fewer conversion stages mean less waste heat inside the white space, directly reducing cooling energy and improving PUE. Less heat in power paths also improves component lifetimes and stability under high rack densities.

Reduced electricity and carbon costs – Higher electrical efficiency and lower cooling translate into substantial Opex reduction over the life of a facility. Because less energy is wasted, DC designs help operators hit sustainability and carbon‑reduction targets.

Supports higher rack power density (AI/GPU) – HVDC (for example ±400–800 V) distributes large amounts of power to tens‑of‑kilowatt racks without oversized copper or bulky AC UPS gear, which is critical for AI “factories.” This enables more compute per rack and per square foot while keeping power distribution manageable.

Smaller footprint and more usable white space – DC gear is typically more compact, reduces transformer and PDU count, and allows lighter cabling, which can cut power‑infrastructure floor space by double‑digit percentages. That freed space can be redeployed for additional racks or cooling infrastructure instead of electrical rooms.

Simpler distribution and fewer failure points – DC power chains have fewer conversion stages, do not require phase balancing, and reduce harmonic issues, which simplifies design and operations. Fewer components and interfaces reduce points of failure and can improve overall system reliability.

Better integration with batteries and renewables – Batteries, fuel cells, and PV arrays are inherently DC, so tying them to a DC bus avoids multiple intermediate conversion steps. This improves round‑trip efficiency for on‑site storage and makes it easier to add solar or other DC sources directly into the data‑center power path.

Improved power quality and stability – DC distribution eliminates many AC‑specific issues (frequency, many harmonics) and can offer more stable voltage at the rack, especially with modern HVDC and modular power electronics. Cleaner, more stable power reduces nuisance trips and stress on sensitive IT equipment.

Modular, scalable growth model – DC architectures (especially rectifier‑plus‑battery strings or packetized/fault‑managed power) can be expanded incrementally as load grows, instead of oversizing AC UPS from day one. This aligns capex with actual demand and makes it faster to add containers, prefabricated modules, or edge sites.

Modern safety and manageability features – New DC and “digital electricity” approaches implement fast fault detection, current limiting, and per‑circuit monitoring, addressing historic safety concerns around HVDC. Centralized digital control over DC circuits also improves visibility, troubleshooting, and SLA compliance in large‑scale facilities.

The Future of DC Data Centers

Historically, one of the earliest companies to build DC data centers was Facebook (now Meta), which has been sharing its data center concepts with the data center industry via the Open Compute Platform (OCP) initiative. Several companies that are part of the OCP initiative are now providing large, containerized DC power “pods” that convert AC to DC and can simply be “plugged in” externally to the data center. There are also companies building filter modules to improve DC power quality within the rack. While not all data centers will go to DC, the large industrial ones are clearly moving in that direction.