This Friday is the 4th of July: How Far Are We From Energy Independence?

What energy independence really means and why fusion may be key to achieving it.

Since the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil crisis of October 1973, it has been the goal of successive U.S. governments to achieve energy independence. Whether you take “energy independence” to mean that we wouldn’t need any imported energy, or that we were a net exporter of energy, it is clear that our need for energy (particularly electricity) is growing rapidly, and will continue to do so for the near future. Interestingly, most of the concepts around “energy independence” focused on petroleum independence. However, the real question that needs to be answered is what source(s) of energy we should be focused on developing for the long-term electrical needs of the U.S. as electricity becomes more important to our economy.

A History Lesson – The Impacts of Energy Prices on Supply

For those of you who have taken basic microeconomics, you are familiar with the law of supply and demand. The law is simple – the market for a product reaches equilibrium where demand and supply match each other at a set price. The concept is rooted in the idea that increasing the supply of a commodity increases the cost of supply (the upward-sloping blue curve), while decreasing the cost of a product will increase the demand for it. While this is often overly simplistic in the face of short-term demand spikes (especially for commodities that cannot be quickly produced, such as food), it is not an unreasonable model over time. Also of interest is the impact of the dynamics of adjacent markets on each other. For instance, if the price of chicken decreases due to more supply, it is likely that the demand for alternatives to chicken (steak, for instance) will go down, which would also result in a price decrease for steak.

In essence, this is what happened to energy commodities from the 1950s on. For instance, the effect of “cheap oil” that was available to U.S. consumers between the 1950 and 1971 resulted in a marked decline in the U.S. coal industry, which went from supplying 51% of the U.S.’s energy down to 19% of the U.S.’s energy (even though coal output increased in absolute terms through 2010). To supply this oil, the U.S. started to import large amounts of oil from the Middle East between 1969 and 1972. This exposed the U.S. oil supply to the political impacts of the various Arab-Israeli conflicts going on during this time, which led to OPEC’s oil embargo of 1973. Similarly, the supply of natural gas has put considerable pressure on the demand for both oil and coal over the last 15 years.

OK, What Does Energy Independence Really Mean Then?

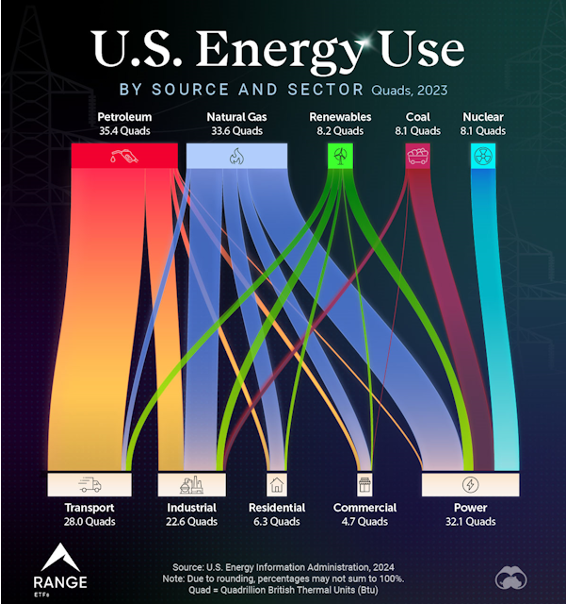

The issue with defining what energy independence means is that a number of sectors of the U.S. economy that use different types of energy, as shown by the graphic below.

Interestingly, the thing that this graph doesn’t capture is the extent to which the “Power” sector is cannibalizing the other energy consuming sectors on the bottom of the graph (primarily Residential, Commercial, and Industrial, but also Transport), as these sectors become increasingly electrified. So as we approach 2050, the question we are increasingly facing is “which energy sources are critical to supplying the power sector, and to what extent are these reliant on imported energy and/or equipment, and how does the availability of each of these affect the availability and prices of each other?”

What Are The Key Sources of Energy for Electricity?

This becomes a “where do we place our bets” type of question in a country (let alone a world) where the demand for electricity is increasing well beyond historical rates? We have already talked about the decline of coal (and oil does not play a significant role in electricity generation) – what are the other key sources, and how “independent” are they in satisfying U.S. electricity demand, which is expected to grow between 30% (US-EIA baseline, shown below) and nearly 75% between 2025 and 2050?

Nuclear Energy: In 2023, nuclear energy is about 18.6% of total U.S. electricity generation. While the total amount of electricity generated by nuclear is expected to stay more or less flat through 2050, the percentage of all U.S. electricity generated by nuclear is expected to drop to roughly 12% by 2050, largely driven by the number of plant retirements between now and 2050 and the amount of time it takes to build new nuclear power plants. From an “energy independence” standpoint, the U.S. imports 95% of its uranium (primarily from Canada, Kazakhstan, and Australia, Russia, and Uzbekistan), so not so independent.

Renewables: Renewables power plants (particularly solar energy plants) are among the quickest to be built, and (usually) are the least affected by permitting issues. This is why the US-EIA baseline forecast predicts that renewables (particularly solar and wind) will provide between 42% and 44% of U.S. electricity by 2050, up from 21% today. The primary issue is that China dominates the worldwide solar panel supply chain, the wind turbine supply chain, and the lithium-ion battery supply chain. While the U.S. is making strides to “reshore” these industries, we have a long ways to go for independence on renewables.

Natural Gas: Of today’s electrical energy sources, natural gas is perhaps the most “independent”. Since 2017, the U.S. has been a net exporter of natural gas, and leads the world in the export of liquified natural gas (LNG). The bulk of the plants themselves (gas turbines, etc.) are also built in the U.S.. Finally, natural gas power plants are both fast and inexpensive to build, making them very attractive, if not as green as the other opportunities above.

Fusion Energy: While not a commercially viable source of grid-scale electricity today, the developments over the last several years have made fusion energy’s commercial availability reasonably close. The expectation is that fusion energy will be commercially available in the mid-2030s, with at least a few prototype plants before the end of this decade. Today, the components for these plants, while at the prototype stage, are built in the U.S., making fusion “independent”.

Summary: Realizing Energy Independence Involves Some Tradeoffs

As someone once said, there is no such thing as a free lunch, and achieving energy independence is no different. In this respect, today’s “cleanest” choices are not necessarily green, and have a number of supply chain vulnerabilities. That is why fusion is attractive – both clean, and with a U.S. supply chain. While fusion won’t supply all of our electricity, it will be an important component to the overall U.S. electricity mix.